Knowing your hardiness growing zone for plants is important if you plan to grow trees, shrubs and perennials. We’ll walk you through exactly what a hardiness zone is, how to find yours, whether or not the new USDA map affects you, how to interpret zones on plant labels, and other factors that affect plants’ hardiness in this detailed article.

If you are thinking about growing hardy plants like trees, shrubs and perennials in your yard, one of the first things you will need to know is what your hardiness zone is. Find your zone by entering your zip code on this map.

What is a hardiness zone?

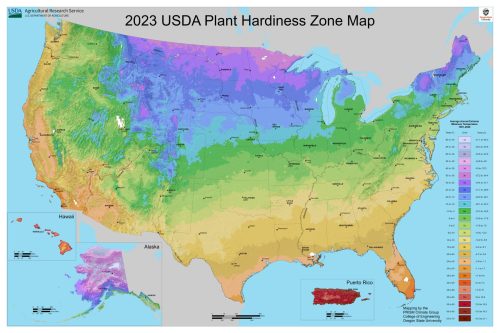

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) sets the hardiness zones for every part of the country and publishes them in a color coded map. These are the official zones that everyone who publishes zones on plant tags, in catalogs, on websites and such use. The hardiness zone map is the one you saw when you entered your zip code on the map in the link above. (If you haven’t tried it yet, stop now and check it out even if you think you know your growing zones for plants. You’ll see why in a moment.)

USDA hardiness zones are based on the average annual minimum winter temperature in 13 zones across the U.S. The lower the zone number, the colder the climate is. For instance, Northern Minnesota is a zone 3 but the southern tip of Florida is a zone 10. Each zone is assigned a 10°F temperature range. The average minimum winter temperature in zone 6 ranges from 0°F to -10°F, but in the much warmer zone 9, the range is 20°F to 30°F.

Each zone is further broken down into A and B, with A denoting the colder half and B denoting the warmer half. So, the average minimum temperature in zone 6a is -5°F to -10°F, and the average minimum temperature in zone 6b is 0°F to -5°F. You may have heard someone say they live in a “cold zone 6”, and that means they live in zone 6a, which is the colder half of USDA hardiness zone 6.

Notice that USDA hardiness zones are based on average annual minimum temperatures. It does not tell the story of the most extreme temperatures ever experienced in those areas, which could have been much colder or much warmer.

Is a hardiness zone the same as my frost-free date?

No, hardiness zones and frost-free dates (also known as last frost date) are not the same thing.

- Your hardiness zone denotes the average minimum winter temperature in your area. That helps you understand which types of plants should be expected to live through the winter outdoors.

- Your frost-free date is the average date by which the last frost of the season is expected to occur. This is the date by which average low temperatures typically remain above 32°F, which is the point at which water can freeze. Tender plants should not be planted outdoors before your frost-free date. Watch your local weather forecast closely in the spring and keep an eye specifically on the nighttime lows. When your actual last frost actually occurs will vary from year to year, often by several weeks, since Mother Nature doesn’t always follow a set calendar.

How do I interpret hardiness zones on a label or your website?

Once you know your hardiness zone, you’ll want to remember it. It will help guide you towards finding plants that will be able to survive the winter in your climates.

Trees, shrubs and perennials are all rated for hardiness. For example, hostas are listed as zone 3 through 9. That means anyone who lives in zone 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 or 9 can grow hostas and expect them to survive the winter. Not all plants have such a broad range of hardiness. For instance, Perfecto Mundo® reblooming azaleas can only survive the winter in zones 6b through 9. So, if you live anywhere colder than zone 6b, Perfecto Mundo azaleas should not be expected to survive the winter for you.

If you are growing annuals, which are tender plants that aren’t expected to survive the winter, you don’t need to bother with knowing their growing zones for plants because you will be pulling them out of your garden at the end of the growing season.

Does my hardiness zone change every year?

No, your hardiness zone should stay the same for most of your lifetime. That’s because historically, the USDA has only revised the hardiness growing zone map a few times per century. Recently, they released the 2023 USDA hardiness zone map which was made using an average of scientific data collected over the last thirty years (1991-2020). It is an update over the last map which was released in 1990.

I heard there was a new hardiness zone map released. Is it more accurate than the old one?

Yes, the new map, which was developed jointly by the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service and Oregon State University’s PRISM Climate Group, is more accurate for today because it uses more recent data collected from nearly 70% more locations – 13,412 weather stations compared to the 7,983 that were used for the old map.

Did my USDA hardiness zone change on the new map?

There’s about a 50/50 chance that your hardiness zone has changed since the new map was published. That’s why we really want you to check to see what your zone is using this tool. About half of the country has shifted to be a half zone hardier, which corresponds to a 1°F to 5°F increase, while the other half experienced no change in zone. This could mean that if your area was previously listed as zone 8a, for example, it may now officially be listed as zone 8b.

There are only a few very small areas in the Mountain West where the hardiness zone shifted a half zone colder. However, those areas are thought to be linked to more sophisticated mapping methods and weather station monitors rather than a shift in the actual climate.

If my USDA hardiness zone changed, can I grow more tender plants now?

The safe answer is no. Remember that the new hardiness growing zone map accounts for slow temperature changes made over the last 30 years and at most, has only warmed by 5°F (one half zone) at most. How long have you been growing plants?

Most plant tags and websites, including our own, do not split hardiness zones into A and B. Rather, a perennial or shrub is said to be hardy in a range such as zones 3-8 or 5-9. A shift of a half of a zone won’t change most of these plants.

If you are risk-averse and don’t want to take the chance of a plant not surviving the winter, it’s best not to start buying less hardy plants even if your USDA hardiness zone has changed according to the new map. However, if you don’t mind taking risks, you are welcome to try something less cold hardy than you have in the past. If it doesn’t live through the winter, you will have learned something new. Lots of gardeners like to “push their zone” now and then and try new plants that might end up in the compost heap. As we like to say, “Zone envy is real!” It is human nature to want what we can’t have.

Other Factors That Affect Plants’ Hardiness

Temperature is a very important factor in predicting whether or not a plant will survive the winter (also known as “overwinter”) in your climate. However, it’s not the only one. Here are a few more that can play an equally important role:

Freeze/Thaw Cycles –

Plants don’t like when temperatures swing drastically within a short period of time. It can send them into shock and kill large portions of a plant back. If the soil freezes and thaws cyclically during the winter, plants could “heave” out of the ground and leave their rootball exposed to the elements. If you see this happen during the winter, do your best to dig the plant back into the ground immediately. If that’s not possible, add more soil on top of the exposed roots and add mulch on top of that to help insulate them until spring arrives and you can work the soil.

Snow Cover –

Snow is one of nature’s best insulating materials. In an ideal world, your ground would freeze in early winter and a blanket of snow would fall and remain there until spring. That doesn’t happen in too many parts of the country, which is why freeze/thaw cycles occur. You might find that you are not able to overwinter some plants rated for your zone if you rarely have snow cover, especially if your area tends to be windy in the winter.

Soil Moisture –

You’ve heard us tout the importance of watering your garden until late in the season, especially evergreen plants and anything new you planted this year. That’s because once the ground is frozen in winter, plants can no longer extract moisture from it. If it’s too dry, your plants can be damaged from desiccation. If it’s too wet, your plants’ roots can rot. For best results, water through the fall and mulch any open ground (shredded leaves work great for this.) Pile the majority of the snow on your lawn instead of on your perennials and shrubs to prevent the soil around their roots from staying too wet for too long.

Timing of Planting and Pruning –

Planting in early fall and up until six weeks before the ground freezes is safe for most perennials and shrubs (borderline hardy plants and evergreens being two exceptions.) However, if plant too late and they don’t have time to develop roots before the ground freezes, they might not survive the winter. Also, some plants are sensitive to fall pruning and that can affect winter hardiness. Plants with evergreen foliage or hollow stems as well as those that are borderline hardy in your area should not be pruned in the fall since it can adversely affect their overwintering.

Microclimates –

A microclimate is a small spot in your landscape that stays either warmer or colder than the rest of the yard. Warmer microclimates usually have a beneficial effect on a plant’s winter survivability. Planting up against a brick wall or the side of your house can create a warm microclimate and may allow more tender plants to survive the cold there. Colder microclimates can have a negative effect. A wind tunnel that’s completely exposed to the elements is an example of a cold microclimate. Even plants that are rated for your hardiness zone may struggle there in the winter.

Prefer to learn about the new USDA hardiness zone map changes by video? Watch Heidi explain these changes. View the Plant Hardiness Zone Map.